Innovative ideas, initiatives, products, culture transformations, have little chance to succeed if they aren’t enabled by smart communications. And it all starts with a simple and easily understood message.

I’m in the process (pre-production) of co-producing a film with a Director friend of mine. The idea for the film wasn’t mine, so one of the first things I asked him after I read the script was: what’s the hook?

That was at the end of October last year. To this day, that question remains unanswered. And as we’ve been casting for the last two weeks, most of the actors have asked us the same question: what’s the hook?

It’s quite embarrassing that potential cast members are asking about the hook, but we have discussed it. The problem is that my Director friend insists that the hook of the movie is: making a low budget movie for nothing and making it look great. You’ll want to watch it because they made it for $X and it looks way more expensive! Then you’ll want to buy the DVD to see the behind the scenes to find out how they pulled it off?!

Of course, that’s not the hook of the movie. That’s the outcome he’d like to happen after people watch the movie. And frankly, nobody cares about that as a hook. People will only be interested in that if they actually like the movie we make and become curious about who made it and how.

For those of you who might not understand the Hook terminology, in simple terms, The Hook is the answer to:

- So what?

- Why should I watch/buy/use it?

- Why should our audience stop what they’re doing and read our story RIGHT NOW?

- What makes it interesting?

- Why should I give a damn?

Pretty simple huh?! Not so. Finding a hook takes effort. Why is it so hard to come up with a hook?

Before I give you the answer, let’s first dig into what motivates people to talk in the first place!

What people talk about an why

People love storylines, it’s almost a sure way to get people to engage and talk. In sports, the media uses storylines to feed our emotions and keep us engaged. Lois Kelly is the author of Beyond Buzz: The Next Generation of Word-of-Mouth Marketing, and she found some key ideas as to what makes people talk.

This is her explanation of the top nine types of stories that people like to talk about:

- Aspirations and beliefs (what we are and what we could be)

- David vs. Goliath (fighting the powerful, common enemy)

- Avalanche about to roll (excitement about being up with the latest trends)

- Contrarian/counterintuitive/challenging assumptions (truth to power)

- Anxieties (our rational…and irrational…fears)

- Personalities and personal stories (interesting or inspirational people to emulate)

- How-to stories and advice (practical advice)

- Glitz and glam (promising to be like those who seem to have it all)

- Seasonal/event-related (contextually based on what’s happening now)

Great, now we have a good idea of what we can tap into to motivate people to talk. Now on to the question at hand: Why is it so hard to come up with a hook?

The Curse of Knowledge

Simplifying a message doesn’t come natural to us. And we have trouble communicating our ideas because our first instinct is to ramble on when we describe our ideas because we think people will want to hear everything about them. But that my friend is not the way to get our point across. Because we know our stuff so well, we fall into the Curse of Knowledge trap:

This so-called curse of knowledge, a phrase used in a 1989 paper in The Journal of Political Economy, means that once you’ve become an expert in a particular subject, it’s hard to imagine not knowing what you do. Your conversations with others in the field are peppered with catch phrases and jargon that are foreign to the uninitiated. When it’s time to accomplish a task — open a store, build a house, buy new cash registers, sell insurance — those in the know get it done the way it has always been done, stifling innovation as they barrel along the well-worn path.

Elizabeth Newton, a psychologist, conducted an experiment on the curse of knowledge while working on her doctorate at Stanford in 1990. She gave one set of people, called “tappers,” a list of commonly known songs from which to choose. Their task was to rap their knuckles on a tabletop to the rhythm of the chosen tune as they thought about it in their heads. A second set of people, called “listeners,” were asked to name the songs.

Before the experiment began, the tappers were asked how often they believed that the listeners would name the songs correctly. On average, tappers expected listeners to get it right about half the time. In the end, however, listeners guessed only 3 of 120 songs tapped out, or 2.5 percent.

The tappers were astounded. The song was so clear in their minds; how could the listeners not “hear” it in their taps?

In order to grow interested in our ideas, people need for us to provide them a hook, a key point they can hang on to that will pull them in. The Hook challenge isn’t exclusive to film-making. It applies anytime we’re communicating an idea, a story, a concept. And when it comes to innovation, a game-changing idea can win or lose depending on how quickly the consumer “gets” it.

So, how can we find and construct a hook for our ideas?

Below are two models I’ve found useful to figure out a hook and construct a message around that key point.

The Made To Stick Model

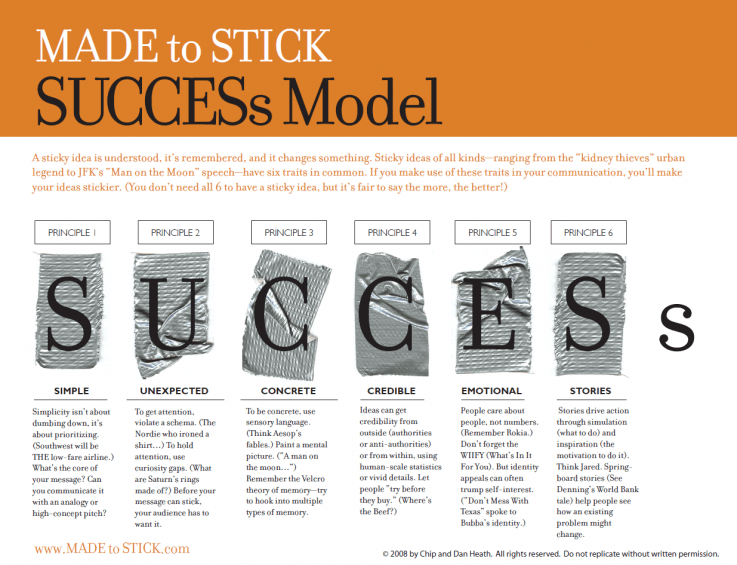

There are no shortage of ideas and books on how to construct an idea that sticks in people’s heads. For me, the most useful concept I’ve found and adopted is the Made to Stick SUCCESs model:

In 2008 Chip and Dan Heath published their outstanding book Made to Stick. The Heath brothers outline six “hooks” that they say are guaranteed to communicate a new idea clearly. And to help people figure out how to do that, they turned the core ideas into the SUCCESs model you see in the picture above.

Here is a brief summary of the core principles:

- Simple: The idea has to be really broken down. Not a cliché, but a simple understandable morsel that you can cognitively digest rapidly. You have to have an easy to get idea. In the book they give the example of Southwest Airlines simple to understand message of “The low-fare airline” to communicate strategy.

- Unexpected: Avoid the obvious. Avoid things that people can see coming a mile and a half away. We want people to be surprised and delighted each time they look at one of our films, and to do that we have to deliberately surprise people.

- Concrete: In addition to being simple, people have to “get it.” People won’t love numbers, but they’ll love real ideas. The myth that someone wakes up in a bathtub full of ice missing a kidney stuck with people because it appealed to the senses. It seemed believable.

- Credible: It’s a counterbalance to unexpected. An idea has to be believable. As much as it is a surprise to people, we have to believe that the idea is true. If people don’t believe in the idea, then it’s simply not true.

- Emotional: You want to believe in something. You want to feel the emotion of something. You must be able to answer the question “What’s in it for me?”.

- Stories: Stories sell, they drive action. Our brains crave stories. People can understand them, relate to them and remember them. A series of facts and figures isn’t remembered without having a story be in context.

Watch the following playlist for a little more substance on what these ideas look like and how they apply to a variety of situations:

Carmine Gallo’s Message Map

In combination with the SUCCESs model, I use Carmine Gallo’s Message Map to construct a 15 second pitch. The message map helps you answer the following question: What is the one thing we want people to know about our service/product?

In the video below, Carmine explains how the Message Map works:

The Message Map is a solid tool that, combined with the SUCCESs model, you’ll find quite useful to find a hook and construct messages that stick.

Bottom line: We all have thousands of options dancing in front of us at all times. A good story has a hook, a compelling reason for the audience to read right now. Communication is everything! Innovations are difficult to explain because nothing like it exists. So, the more hooks our idea has the more likely people will hold on to it.